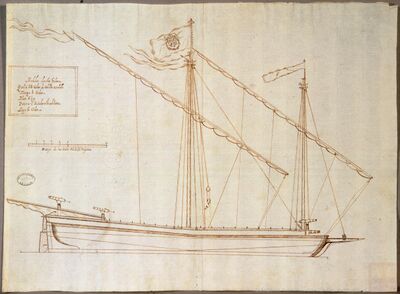

Guardacostas

The Caribbean basin and North American seaboard remained fundamentally violent places as British pirates and Spanish-American corsairs—guardacostas—plundered shipping with near impunity. And although Anglo-American pirates were crushed by the early 1720s, Cuban guardacostas remained a menace, seizing vessels of all nations in the Caribbean and along the eastern seaboard. They were commissioned by Spanish authorities to combat smuggling, but found it safer and more profitable to target any foreign vessel they found. Over two hundred Anglo-American and countless more Dutch and French vessels were seized by Spanish corsairs in the three decades after 1710.

Details

The Armada de Barlovento—Spain’s permanent naval squadron in the Caribbean, with its headquarters alternating between Havana and Veracruz—in the early 1730s, consisted of only four ships. While sufficient for the Armada’s main employment of transporting situados—silver used for the payment of garrisons and governmental expenses in Spain’s West Indian colonies—and escorting the treasure fleets across the Atlantic during peacetime, those obligations consumed the entirety of its meager resources. Between 1724 and 1732 officials dispatched two warships from Spain to patrol the coast of Colombia and Venezuela for smugglers.

Guardacostas, like privateers, combined a measure of public management with private capital, since the Crown could not afford to maintain patrol vessels from its own purse. Initially created to combat the buccaneers and pirates of the seventeenth-century, by the 1700s, guardacostas’ purpose was primarily the pursuit of contrabandists. Individuals would offer to outfit a guardacosta in exchange for a share of the proceeds from any seizures made. Santiago de Cuba in the east and Trinidad on Cuba’s southern coast swiftly became major bases of these vessels. From the perspective of Spain’s imperial economy, the governors' primary responsibility lay with protecting the galleons rather than limiting foreign imports. If confiscation of one foreign vessel would frighten the others away from the port, a governor might sacrifice his ability to provide for coastal defense by vigorously prosecuting the contraband trade. In reality, they were given a largely free hand in pursuing suspected smugglers, as well as granting them the coveted fuero militar—legal protection from civil courts. The result was frequent seizures and plundering of Anglo-American shipping, often on the flimsiest of pretexts such as the presence of Spanish coins or a few sticks of logwood. The scale of Anglo-Spanish trade in the region and the widespread practice of using dyewoods as ballast on European-bound voyages meant that almost every vessel carried at least one of those damning commodities—even if they had never been near a Spanish colony. Although there were never more than twenty guardacostas operating simultaneously in the West Indies, they were nevertheless the terror of merchants and seamen of the other Atlantic empires.

An armador (outfitter) was to provide a sufficient—unspecified—security to the local Governor or Viceroy for his good behavior and in return was granted a patente del corso (letter of marque) to outfit a ship or ships. When the guardacosta seized a foreign ship, the captain was to carry it into the port from whence the he sailed, to be tried. In principle, this requirement served as a check on corsairs, for if the prize was determined to have been improperly taken, the armador and his security would be close at hand to make proper restitution. But, creating a massive loophole, the Crown also granted that, if the captors were unable to easily carry a prize into their home port, they could instead sail it to the nearest Spanish harbor. That is, it allowed guardacostas to carry their prizes to a port where they knew they could find sympathetic judges—ones willing to ask few questions about the legitimacy of a prize in return for a share of its value. Furthermore, the Instruction’s Article 11 granted civil and criminal jurisdiction over the guardacosta and its crew during the voyage to the armador, removing the danger of the crew being tried in court for any crimes they committed while aboard the privateer. Commissions were normally granted for six months at a time and, while enjoining the privateer to act against enemies of the Spanish Crown, they gave no specific guidelines to who such enemies were.

- Trinidad’s prominence as a guardacosta nest faded in the 1720s. In 1721, many of the town’s leaders were arrested for smuggling—clear evidence that the contraband trade and the sponsorship of privateers were not seen as mutually exclusive investments. Then, when in 1725 the town asked the Governor in Havana for permission to issue a half dozen patentes de corso, they were summarily refused, because, as the Governor explained the town was notorious for its privateers raiding Spaniards as well as foreigners. Even worse, the alcaldes consistently failed to supply the Governor with information regarding the vessels fitted out or seized, nor did they dispatch the Crown’s share of prizes to Havana.

- Maps were issued describing standard travel routes between foreign ports, that if a foreign vessel were found outside them, it might be considered "suspicious."

Practices

Cuban-based guardacostas concentrated on the Windward Passage between eastern Cuba and Saint Domingue and the Florida Channel; the main routes by which vessels departing Jamaica travelled. They also patrolled the Bahamas, which Spain still laid claim to, frequently seizing salt gatherers at Turks Island. Puerto Rican privateers terrorized the Leeward Islands, and frequently cruised along the southern coast of Hispaniola, seizing vessels coming from Europe to Jamaica. Vessels fitted out from Cuban ports also raided Jamaica’s northern coast for slaves.

Any foreign vessel found not travelling directly to or from its colonies was considered suspicious, particularly if within sight of Spanish lands. Such a voyage was considered to be undertaken in rumbos sospechosos (literally “suspicious courses”). The vessel could therefore be stopped and searched by any Spanish official. The policy took no account of travel between foreign colonies, and almost as little to the vagaries of wind and weather. Although foreign powers, particularly the British, maintained that a vessel could be stopped and searched for illicit trade only if it was found immediately off a Spanish shore and actively trading, Spanish officials maintained a much more expansive view of when and where a vessel could be seized.

When it stopped a foreign vessel, generally with a warning shot, the guardacosta would dispatch a small boat to board and examine the foreigner for contraband goods. The captain’s cabin, the hold, and the personal lockers of crew and passengers were all searched for items that could have come from Spanish territories. Silver coins, cochineal, cacao, and, most commonly, logwood or “brazil wood” were all considered evidence of potential illegal trade, even if the vessel’s papers revealed it had last sailed from a non-Spanish colony. Such claims meant little, for, culturally and legally, Spanish officials believed that items possessed something akin to a vitium reale—an inherent taint characteristic in the item itself. In their view, a product was forever marked by its country of origin; once a Spanish product always a Spanish product.

Before a prize and its cargo could be properly sold, and the captors assured of their protection from any foreign complaints, it had to be legally condemned at trial. In this process, the ship was to be carried to port, the cargo inspected and inventoried by officials, and depositions taken from both captors and prisoners. Then the judge would make his decision. Spanish judges, particularly in the “piratical ports” of Trinidad and Baracoa, and at times Havana and Santiago de Cuba as well, were themselves often investors in guardacostas and were not likely to view seized vessels with much criticism. They were aided by the fact that guardacostas commonly abandoned most of their prisoners at sea before returning to port—leaving fewer voices to testify. After condemnation, the seized vessel and its cargo were sold, or taken by the privateers to replace their own vessels, and the captured Anglo-Americans left to find their own way home—often with the help of South Sea Company factors. Despite the histrionics of the London press, few British sailors were put to hard labor on Spanish fortifications or rotted in Spanish prisons.

- Like more "traditional" pirates, the crew aboard a guardacosta worked not for wages, but for shares of prizes. This created incentives to seize any vessel they encountered. Although bloodless captures were the norm, under such pressure violence and torture were a not uncommon way to convince captured crews to reveal hidden cargo or personal effects. Even a few coins in a captain’s chest were held as sufficient evidence to bring a vessel in for trial and condemnation.

- Using tactics akin to pirates, they approached their prey under friendly colors before revealing their true identities and boarding them.

- Invariably, even if a vessel was released, it would be plundered; crewmen and passenger’s clothing was especially vulnerable—a sign of the value and shortage of European textiles in Spanish Caribbean islands.

- This practice was very common among guardacostas that the witnesses were often augmented by one of the captors who happened to be English, or more commonly Irish, claiming to have been a crewman on the prize and that it had come to trade illegally.

Foreign Response

Due to the dangers of Spanish guardacostas, the sloops that made up the majority of smuggling vessels were “fitted out in a defensible and expensive manner” with a minimum of two dozen crewmen—and often twice that number—and an average of eight guns. To encourage the crew to fight when confronted by Spanish authorities, wages were high—nearly £3 sterling per month—and at least in some instances sailors were also allowed to carry their own small bundle of goods to sell.

At the same time as they were supplying the Spanish with guardacostas, the South Sea Company’s factories were sources of aid and succor to the Anglo-Americans who were their victims. The Cuban factories were most active in this regard due to the high number of prizes brought into those ports. When a prize was brought in, factors frequently represented the victims before the governor, arguing that any Spanish coin aboard came from dealings with the Company’s agents in Jamaica. On the frequent occasions when a vessel was condemned, the factors provided food, shelter, and travel to Jamaica out of their own pockets.

Apart from sending warships to hunt down guardacostas, the "official" response was two-fold. Upon news of a captured vessel, authorities drafted letters that demanded justice and the release of the ship, and sent them to officials at the Spanish port where condemnation occurred. Almost without exception, Spanish officials would refuse to release the ship, because either there was in their view clear evidence it was an illicit trader, or, more commonly, they needed orders from Spain to do so. The expense and time of waiting for such orders—if they ever appeared—meant that most Anglo-American traders soon abandoned such efforts for redress. Simultaneously, the British Navy waged an unofficial war against guardacostas. Branding them as pirates no different than their more famous Anglo-American contemporaries, they held trials of captured guardacostas in Port Royal, Nassau, and even New York. Upon conviction, they either hung the captured Spaniards or sold them into slavery if they were of African descent.

In the years following the Peace of Utrecht, a common pattern had emerged. When an Anglo-American vessel was seized in the Caribbean by guardacostas, its crew, who had either been deposited on non-Spanish islands or been allowed to depart Spanish territory with the assistance of the South Sea Company’s factors, would make their way to Jamaica or Antigua. There, they petitioned the local magistrate for aid. Along with a letter from the Governor demanding redress, their depositions were passed on to the local naval commander who, in turn, then ordered one of his ships to sail to the port in whose jurisdiction the vessel had been condemned and demand the release of the vessel and restitution for the owners’ losses. These missions of redress almost invariably ended in failure.

Frequently, the merchants who owned a seized vessel would also take their complaints to England where their case would be forwarded on to the British Minister in Spain for redress. This, too, was futile. Spanish Ministers usually refused to take any action until they received copies of trials from America. This was not just obstreperousness, of course, for the statements presented by the merchants in London were often very different from those in Cuban trial records, and it was often impossible to reconcile the two. Exasperated by such discrepancies, Minister Plenipotentiary Benjamin Keene is known to have exclaimed upon receiving a bundle of such questionable claims: “my God what roofs!...Are the oaths of fellows that forswear themselves at every custom-house in every port they come to, to be taken without any further enquiry or examination?”

- The Dutch were particularly notorious for their aggressiveness against guardacostas, often fitting out vessels to pursue them and rarely taking prisoners.

Known guardacostas around 1725

- Augustin Blanco, 1700-1725 Cuba He was noted for attacking in open boats, and for having a mixed-race crew.

- Don Benito (fl 1725, real name possibly Benito Socarras Y Aguero) was a Spanish pirate and guardacosta privateer active in the Caribbean.

- Don Miguel Enríquez (Henríquez) 1674–1743 1701–1735 Puerto Rico Although born a shoemaker, Enríquez was later awarded a letter of marque by Spain, going on to become knighted and gathering a fortune of over 500,000 pieces of eight. Considered the "most accomplished" of the Hispanic privateers.

- Juan León de Fandiño, guardacosta active during the Anglo-Spanish War (1727-29), responsible for the War of Jenkin's Ear in April 1731

- Nicholas Brown, d. 1726 to 1726 England Active off the coast of Jamaica, Brown was eventually killed – and his head pickled – by childhood friend John Drudge.